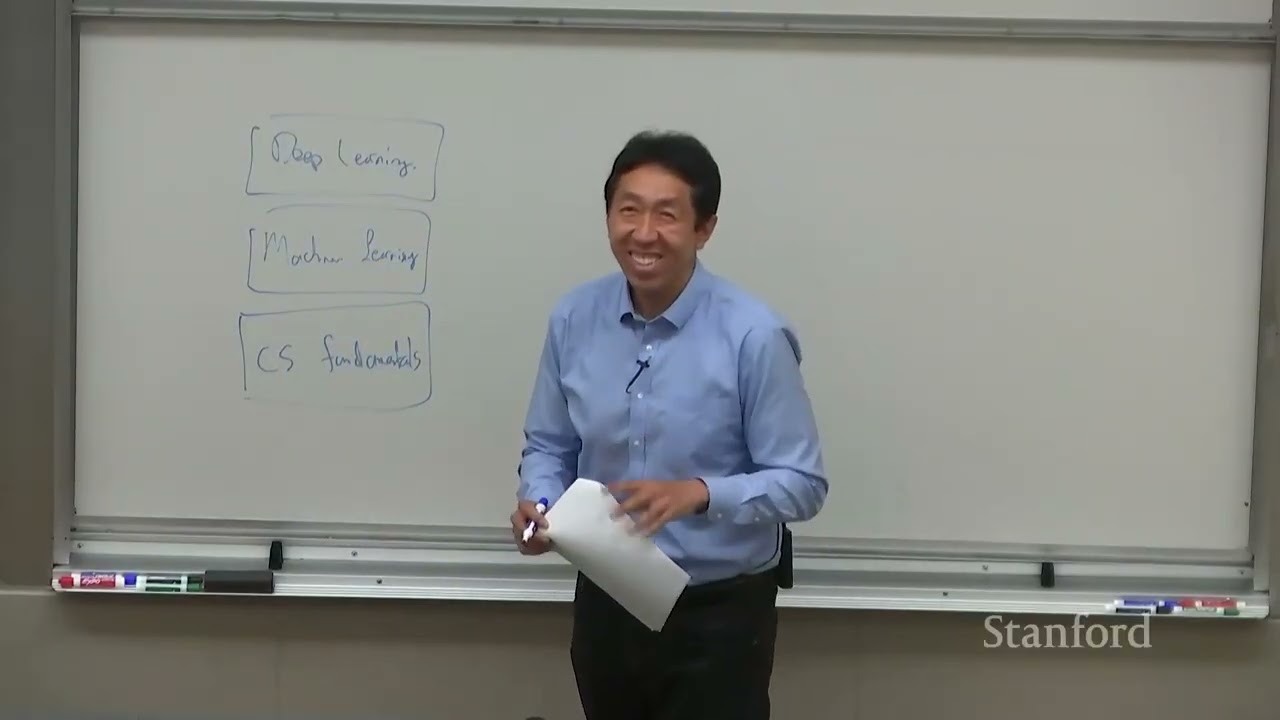

Stanford CS230 | Autumn 2025 | Lecture 1: Introduction to Deep Learning

BeginnerKey Summary

- •This lecture kicks off Stanford CS230 and explains what deep learning is: a kind of machine learning that uses multi-layer neural networks to learn complex patterns. Andrew Ng highlights its strength in understanding images, language, and speech by learning layered features like edges, textures, and objects. The message is that deep learning’s power comes from big data, flexible architectures, and non-linear functions that let models represent complex relationships.

- •You learn the course structure: Part 1 covers the foundations—neural networks, backpropagation, optimization, and regularization. Part 2 focuses on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for images, including object detection and segmentation. Part 3 moves to recurrent neural networks (RNNs) for sequences, such as language, speech, and time series.

- •Logistics are clear and demanding: four programming homeworks, a midterm on theory, and a final project that applies deep learning to a real problem. Grading is 40% homeworks, 20% midterm, and 40% final project. You’ll use Python and TensorFlow, get help via office hours/sections, and a Q&A forum.

- •The lecture introduces the single-layer perceptron: compute z = w^T x + b, then apply an activation function a = g(z). Activation functions like sigmoid, ReLU, and tanh make the model non-linear, which is essential for solving real-world problems. Without them, the model is just a straight-line (linear) predictor.

- •Training is done with gradient descent, which iteratively nudges weights and bias downhill on the error surface. The update rules are w := w − α ∂E/∂w and b := b − α ∂E/∂b, where α is the learning rate controlling step size. This method improves the model by reducing the gap between predictions and true labels.

- •Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) stack layers of neurons: input, hidden, and output layers. Each layer computes z^(l) = W^(l) a^(l−1) + b^(l) and then a^(l) = g(z^(l)); stacking creates non-linear decision boundaries. With hidden layers, the network can learn complex, hierarchical representations.

- •Backpropagation is introduced as the algorithm that computes gradients efficiently for all weights and biases. It does a forward pass to compute activations, then a backward pass to propagate errors and compute partial derivatives. This makes training deep networks practical and scalable.

- •Real-world applications show why deep learning matters: image recognition for self-driving cars and medical diagnosis, NLP for translation and chatbots, and speech recognition for virtual assistants and transcription. These advances became possible through big datasets, better compute, and architectures like CNNs and RNNs.

- •The course balances theory and practice so that you understand why methods work and can build models yourself. Expect to write code in Python and TensorFlow to implement concepts like forward passes, loss functions, and gradient updates. Tutorials will be available to help you ramp up.

- •Key math ideas include vectors of inputs (x), weights (w), bias (b), activation functions g(), and layer-by-layer transformations. You learn why non-linearity is essential: without it, multiple layers would collapse into one linear transformation. This insight motivates activation choices and network depth.

- •The lecture emphasizes disciplined learning: prepare for time commitment, seek help early via office hours, and use the forum for peer learning. The final project is your chance to demonstrate end-to-end skills, from data handling to training and evaluation. Clear milestones (homeworks, midterm, project) guide your progress.

- •By the end of the lecture, you know what deep learning can do, how this course will teach it, and what’s expected of you. You also have the core mental model of a neuron (weighted sum + non-linear activation) and the training loop (forward pass + gradient descent + parameter updates). Next lectures dive deeper into backpropagation, CNNs, and RNNs.

Why This Lecture Matters

This lecture is essential for anyone starting deep learning—students, engineers pivoting into AI, data scientists expanding from traditional ML, and product builders scoping AI projects. It clarifies what deep learning truly is, why it has surged in impact, and how to approach learning it in a structured, practical way. Understanding perceptrons, activations, gradient descent, and backpropagation gives you the mental toolkit to reason about any neural architecture, from simple MLPs to advanced CNNs and RNNs. In real work, these basics help you debug training failures, choose sensible activations and learning rates, and plan data and compute needs. The course logistics and project emphasis map directly to industry practice: you’ll build end-to-end systems, evaluate results, and iterate, mirroring applied AI development. In today’s industry—where AI powers vision in cars and hospitals, language in assistants and support, and speech in dictation and accessibility—knowing these fundamentals opens doors to impactful roles and research. Starting with a rock-solid foundation keeps you from treating deep learning as a black box and enables you to design, train, and deploy models with confidence and accountability.

Lecture Summary

Tap terms for definitions01Overview

This opening lecture of Stanford CS230, taught by Andrew Ng, introduces deep learning, sets the course roadmap, explains logistics and expectations, and begins the technical foundations with perceptrons, activation functions, gradient descent, multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs), and backpropagation. It starts by defining deep learning as a subset of machine learning that uses neural networks with many layers to learn complex, hierarchical representations from data. A practical intuition is given through images: early layers detect simple edges, later layers detect textures and parts, and deeper layers recognize whole objects. The lecture emphasizes why deep learning has become so powerful: access to large datasets, flexible architectures that can be adapted to many tasks, and the capacity to model non-linear relationships.

The course is structured in three parts. Part 1 builds the foundation: neural networks, backpropagation (the algorithm to compute gradients efficiently), optimization algorithms (like gradient descent variants), and regularization techniques (methods to reduce overfitting). Part 2 focuses on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for visual tasks including image recognition, object detection, and segmentation. Part 3 introduces recurrent neural networks (RNNs) to handle sequential data such as natural language, speech, and time series. Throughout, the course balances theory and hands-on practice, using Python and TensorFlow as the main tools. Students are encouraged to brush up on these technologies with provided tutorials and external resources.

Logistics are set with clear expectations: the class is demanding and requires consistent effort. There are four programming homeworks providing hands-on experience, a midterm exam testing theoretical understanding, and a final project where students apply deep learning to a real-world problem. Grading weights are 40% for homeworks, 20% for the midterm, and 40% for the final project. Support includes section leading meetings/office hours for one-on-one help, plus an online Q&A forum for community-driven assistance.

The technical portion of the lecture begins with the single-layer perceptron, the simplest neural network building block. Each neuron computes a weighted sum of inputs plus a bias, passes it through a non-linear activation function, and produces an activation (output). Common activation functions include sigmoid (outputs between 0 and 1), ReLU (outputs 0 for negative inputs and the input itself for positive inputs), and tanh (outputs between −1 and 1). The lecture explains why activation functions are essential: they introduce non-linearity, allowing the model to learn beyond straight-line relationships. Training a perceptron involves finding weights and bias that minimize prediction error, using gradient descent to iteratively update parameters in the direction that most reduces the error.

The lecture then generalizes to multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs), which stack multiple layers: input, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. Each layer transforms the previous layer’s activations using its own weights, bias, and activation function. The crucial difference from a single-layer perceptron is that hidden layers allow the network to represent highly non-linear decision boundaries and hierarchical abstractions of data. Finally, the backpropagation algorithm is introduced as the key method to compute gradients for all weights and biases efficiently by doing a forward pass (compute activations) and a backward pass (propagate errors and compute derivatives).

By the end of this lecture, you know what deep learning is, where it’s used (image recognition, NLP, speech recognition), why it has become impactful, and how this course will build your knowledge step-by-step. You also gain the foundational equations of neurons and the training loop (forward computation and gradient-based updates), preparing you for deeper dives into optimization, regularization, CNNs, and RNNs in the coming sessions. The lecture’s core message is that deep learning’s strength lies in learning layered, non-linear representations from data, and that with disciplined study and practice, you can master these tools to solve meaningful real-world problems.

02Key Concepts

- 01

What Deep Learning Is: Deep learning is a branch of machine learning that uses many-layered neural networks to learn complex patterns from data. Think of it like building with Lego bricks where small patterns stack into bigger ones—edges become textures, then objects. Technically, each layer transforms inputs with weights, bias, and a non-linear activation function, allowing multiple levels of abstraction. This matters because many real-world tasks are not simple straight lines; they need rich, layered reasoning. Example: recognizing a cat in a photo requires combining whiskers, fur texture, ear shapes, and overall silhouette—deep networks learn these steps automatically.

- 02

Why Deep Learning Became Powerful: It thrives with large datasets, flexible architectures, and non-linear modeling capacity. Imagine an athlete who gets better the more they practice and can switch sports easily—deep networks improve with more data and adapt to many tasks. Technically, increased compute, GPU acceleration, and vast labeled datasets enabled training deeper models with millions of parameters. Without these, earlier methods would hit limits on complex tasks. Example: ImageNet-scale data made it possible for CNNs to outperform traditional computer vision features.

- 03

Hierarchical Representation Learning: Layers learn simple-to-complex features over depth. It’s like reading: first letters, then words, then sentences, then stories. In neural terms, early layers detect edges, mid-layers detect textures and parts, and deeper layers recognize full objects or concepts. Without hierarchy, models would struggle to capture high-level structure from raw pixels or raw audio. Example: In speech recognition, early features capture frequencies, later ones capture phonemes, and deeper layers capture words.

- 04

Course Structure—Part 1 Foundations: The first part covers neural networks, backpropagation, optimization algorithms, and regularization techniques. Think of it as learning the rules of the game before playing competitively. Technically, you’ll understand neurons (weighted sums + activations), compute gradients with backprop, and update parameters with gradient descent variants. This baseline matters because all advanced architectures build on these ideas. Example: Knowing how to compute ∂E/∂W is required before you can train CNN filters.

- 05

Course Structure—Part 2 CNNs for Vision: The second part focuses on convolutional neural networks for image tasks like recognition, object detection, and segmentation. It’s like giving the network special eyes that look for patterns in small patches and reuse them across the image. Convolution and pooling reduce parameters and exploit spatial structure efficiently. Without CNNs, fully-connected models would be too big and lose locality information. Example: Detecting pedestrians in self-driving improves by scanning learned filters across frames.

- 06

Course Structure—Part 3 RNNs for Sequences: The third part teaches recurrent neural networks for language, speech, and time series. Think of an RNN as a reader that remembers what came before to understand the next word or sound. Technically, it maintains a hidden state that updates with each time step, modeling sequential dependencies. This matters because sequences carry context over time; independent snapshots miss meaning. Example: Correctly transcribing homophones in speech requires remembering prior words for context.

- 07

Course Logistics and Grading: The course includes four hands-on homeworks, a midterm on theory, and a final project; grading is 40/20/40. Treat it like training for a marathon: steady weekly work beats last-minute sprints. You’ll code in Python with TensorFlow, use office hours and the forum for help, and follow posted tutorials to ramp up. Clear milestones help you plan and get feedback early. Example: A homework might ask you to implement forward/backward passes for a tiny MLP and compare activations.

- 08

Single-Layer Perceptron—Neuron Computation: A perceptron computes z = w^T x + b and then a = g(z), where g is a non-linear activation. Imagine a decision thermometer: it sums up signals (x) weighted by importance (w), nudged by bias (b), then passes through a shaping function (g). Mathematically, this is an affine transform followed by non-linearity, mapping inputs to outputs. It matters because this is the core unit from which bigger networks are built. Example: Predicting if an email is spam using features like word counts as inputs.

- 09

Activation Functions—Sigmoid, ReLU, Tanh: Activations bend straight lines into curves, enabling non-linear decisions. Like a light dimmer (sigmoid) or a half-wave rectifier (ReLU), they shape the output response. Sigmoid outputs in (0, 1), ReLU outputs max(0, z), and tanh outputs in (−1, 1). Without them, stacking layers collapses to a single linear transform, losing expressive power. Example: Using ReLU speeds learning and helps deep models detect complex visual features.

- 10

Why Non-Linearity Is Essential: Non-linearity lets networks draw complex decision boundaries. Picture trying to separate a swirl of red and blue dots with a straight line—impossible without curves. Technically, linear layers composed together are still linear; non-linear activations break this limitation. This matters for capturing interactions between features. Example: Classifying moons- or circles-shaped datasets needs non-linear boundaries.

- 11

Training with Gradient Descent: Gradient descent iteratively updates parameters to reduce error. It’s like walking downhill in fog, taking steps guided by the slope beneath your feet. Technically, w := w − α ∂E/∂w and b := b − α ∂E/∂b; α is the learning rate controlling step size. Without gradient descent, finding good parameters in high-dimensional space would be impractical. Example: Starting from random weights, repeated updates gradually improve accuracy on labeled data.

- 12

Learning Rate—Step Size Matters: The learning rate α sets how big each update is during training. It’s like adjusting the volume: too loud (large α) and things crash; too soft (small α) and nothing changes. Mathematically, α multiplies the gradient to scale parameter updates. Choosing α poorly can stall training or cause divergence. Example: Trying α = 0.1 might overshoot; α = 0.001 might converge smoothly.

- 13

Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP): An MLP stacks layers: z^(l) = W^(l) a^(l−1) + b^(l), a^(l) = g(z^(l)). Think of it as an assembly line where each station transforms its input and passes it on. Technically, depth and non-linearity enable complex function approximation and hierarchical feature learning. This matters because many tasks need multiple abstraction levels to solve well. Example: A 3-layer MLP can learn XOR, which a single linear layer cannot.

- 14

Forward and Backward Passes: The forward pass computes activations layer by layer; the backward pass propagates errors to compute gradients. It’s like first running a factory to produce outputs, then retracing steps to see how to improve each station. Mathematically, backprop applies the chain rule efficiently across layers. Without this, computing all partial derivatives would be too slow. Example: After a forward pass, the loss gradient at the output propagates back to adjust each W^(l), b^(l).

- 15

Error/Loss Minimization: Training targets minimizing a loss that measures the gap between predictions and true labels. Loss is like a report card score—lower is better. Common losses (though not detailed here) connect to gradient signals the optimizer uses. Minimizing loss aligns model outputs with desired behavior. Example: For binary classification with sigmoid outputs, cross-entropy loss penalizes confident wrong predictions strongly.

- 16

Applications—Image Recognition: Deep models reach high accuracy in recognizing objects and scenes. Think of them as teaching a computer to see patterns like we do. CNNs exploit spatial structure to find edges, textures, and objects across an image. Without deep learning, handcrafted features struggled with variability. Example: Self-driving cars detect pedestrians and traffic signs in real time.

- 17

Applications—Natural Language Processing (NLP): Deep learning understands and generates human language. It’s like teaching a computer to read and write with context. RNNs (and other sequence models) track word order and meaning over time. This unlocks translation, chatbots, and summarization with high quality. Example: Translating a sentence requires remembering earlier words to choose the right later words.

- 18

Applications—Speech Recognition: Models convert audio waves to text with high accuracy. Imagine a scribe that listens and types simultaneously. Sequence models process temporal patterns in sound, mapping them to phonemes and words. This enables assistants, dictation, and transcription services. Example: Saying “Set an alarm for 7 AM” is recognized reliably across different accents.

- 19

Tools—Python and TensorFlow: The course uses Python for programming and TensorFlow for building and training neural networks. It’s like using a universal language (Python) with a powerful construction kit (TensorFlow). Technically, TensorFlow handles tensors, automatic differentiation, and optimization routines. These tools reduce boilerplate so you can focus on model design. Example: Defining layers and training loops is concise with high-level APIs.

- 20

Course Support—Office Hours and Forum: Help is available through sections/office hours and an online Q&A forum. Think of it as a study team with coaches and peers. Early questions prevent small confusions from becoming big blockers. Using these resources boosts understanding and project success. Example: Posting a bug trace on the forum often gets quick, targeted suggestions.

- 21

Time Commitment and Discipline: The course is demanding and requires consistent weekly effort. It’s like learning an instrument—you improve steadily with regular practice. Planning time for lectures, readings, coding, and debugging is essential. Without structure, deadlines creep up and lower learning quality. Example: Setting aside fixed blocks for each homework phase (data, model, training, report) helps you finish strong.

- 22

Backpropagation—Core Training Algorithm: Backprop efficiently computes gradients for all parameters using the chain rule. Picture a message passed backward through each layer, telling it how much it contributed to the final error. Technically, the algorithm stores intermediate activations during the forward pass, then uses them in the backward pass to compute ∂E/∂W and ∂E/∂b. This efficiency enables training deep networks with many layers. Example: Computing gradients layer-by-layer avoids recomputing from scratch for each parameter.

- 23

Non-Linear Decision Boundaries: Adding hidden layers and activations lets models draw complex, curvy boundaries between classes. It’s like switching from a ruler to a flexible curve when separating colored marbles on a table. Composing linear transforms with non-linearities approximates intricate functions. This is crucial when classes overlap in feature space. Example: The classic XOR problem is solvable with a small MLP but not a single linear layer.

- 24

From Perceptron to Deep Nets: The perceptron is the fundamental unit; stacking them yields deep models. Think of neurons as tiny calculators that, when combined, can solve big problems. Technically, each neuron contributes a non-linear basis function to the network’s overall function. Without stacking, you cap the model’s expressiveness. Example: Moving from a 1-layer to a 3-layer MLP dramatically increases what functions you can approximate.

03Technical Details

Overall Architecture/Structure of Concepts Introduced:

- Single-Layer Perceptron (SLP)

- Role: The perceptron is the basic computational unit of neural networks. It maps an input vector x ∈ R^d to an output a via two steps: an affine transform z = w^T x + b, then a non-linear activation a = g(z).

- Data Flow: Inputs (features) enter as x. Parameters include the weight vector w and bias b. The neuron computes z, then applies an activation function g to produce a. In classification, a may be a probability-like score (e.g., with sigmoid) or a transformed feature for deeper layers.

- Why Non-Linearity: If g were the identity (no activation), the model would be linear: any composition of linear transforms is still linear. Real tasks need non-linear decision surfaces; hence g must be non-linear.

- Activation Functions

- Sigmoid: g(z) = 1 / (1 + e^(−z)), output in (0, 1). Useful when outputs are interpreted as probabilities; has smooth gradients but can saturate for large |z|.

- ReLU: g(z) = max(0, z). Efficient, reduces vanishing gradients for positive z, sparse activation; can cause “dead” neurons if inputs stay negative.

- Tanh: g(z) = (e^z − e^(−z)) / (e^z + e^(−z)), output in (−1, 1). Zero-centered, but can still saturate for large |z|. Choice of activation affects training dynamics, gradient flow, and performance.

- Loss/Error and Gradient Descent Training

- Objective: Minimize a loss E(w, b) that measures discrepancy between predictions and labels. The exact loss wasn’t specified here, but common ones include mean squared error (MSE) for regression and cross-entropy for classification.

- Gradient Descent Update: Repeatedly update parameters by moving opposite to the gradient: w := w − α ∂E/∂w; b := b − α ∂E/∂b. α is the learning rate; it scales the step size.

- Iteration Loop: For each batch or dataset pass, compute predictions (forward pass), compute loss, compute gradients (backward pass or analytic derivatives for SLP), then update parameters.

- Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP)

- Layers: Input layer a^(0) = x; for l = 1..L: z^(l) = W^(l) a^(l−1) + b^(l), a^(l) = g(z^(l)). W^(l) is a matrix mapping from layer l−1 to l; b^(l) is the bias vector.

- Expressiveness: With enough hidden units/layers and appropriate activations, MLPs can approximate very complex functions (universal approximation). Hidden layers create non-linear feature transformations.

- Output Layer: May use sigmoid for binary classification, softmax (though not spelled out here) for multi-class, or linear for regression.

- Backpropagation (High-Level)

- Purpose: Efficiently compute gradients ∂E/∂W^(l) and ∂E/∂b^(l) for all layers.

- Mechanism: Store activations and pre-activations during forward pass. During backward pass, compute output layer error signal (e.g., δ^(L) = ∂E/∂z^(L)), then recursively propagate to earlier layers via δ^(l) = (W^(l+1))^T δ^(l+1) ⊙ g′(z^(l)), where ⊙ is elementwise multiplication. Then gradients are ∂E/∂W^(l) = δ^(l) (a^(l−1))^T and ∂E/∂b^(l) = δ^(l).

- Efficiency: Avoids redundant computations by reusing stored forward-pass values. Complexity scales linearly with number of parameters.

Detailed Explanation of Each Component: A) Inputs, Weights, and Bias

- Inputs x: A vector of features representing the sample. For images, this could be pixel intensities; for text, it could be counts or embeddings; for audio, spectral features.

- Weights w (or W): Learnable parameters that scale and combine inputs. Intuitively, each weight indicates how much its corresponding input contributes to the neuron’s decision.

- Bias b: A learnable offset allowing the activation function’s threshold to shift independently of the inputs, enabling the model to fit patterns not passing through the origin.

B) Activation Function Behavior and Choice

- Sigmoid Pros/Cons: Pros include probabilistic interpretation and smoothness; cons include saturation (gradients approach zero for large |z|) and lack of zero-centering which can slow optimization.

- ReLU Pros/Cons: Pros are computational simplicity, reduced vanishing gradient for z > 0, and sparse activations that can regularize implicitly. Cons include dead neurons when weights/biases force z < 0 persistently, and unbounded positive outputs.

- Tanh Pros/Cons: Zero-centered outputs can aid optimization; still suffers from saturation in extremes. Often used historically, now frequently replaced by ReLU-family activations in deep networks.

- Importance: The activation directly shapes the gradient signal g′(z), affecting training speed and stability.

C) Gradient Descent Mechanics

- Gradient Interpretation: ∂E/∂w_i tells how much the loss would change if weight w_i changed slightly. Moving in the negative gradient direction reduces the loss most rapidly (locally).

- Learning Rate Tuning: α too large causes oscillations or divergence; α too small slows training. Practical strategies (not covered here) include decay schedules or adaptive methods, but the core idea is to pick α that steadily decreases loss.

- Stopping Criteria: Iterate until convergence (loss stabilizes), a set number of epochs, or validation performance stops improving.

D) Forward Pass in MLPs

- Step-by-Step: Given input a^(0) = x, compute z^(1), a^(1), then z^(2), a^(2), and so on until z^(L), a^(L). The final a^(L) is the prediction.

- Data Shapes: If a^(l−1) has n_(l−1) units and a^(l) has n_l units, then W^(l) is n_l × n_(l−1), b^(l) is n_l × 1, a^(l−1) is n_(l−1) × 1, and a^(l) is n_l × 1.

- Vectorization: Implementations compute many samples in parallel by stacking inputs into matrices (batches). This uses efficient linear algebra operations.

E) Backward Pass in MLPs (Conceptual)

- Output Error: Compute δ^(L) from the derivative of the loss with respect to z^(L). For example, with a sigmoid output and cross-entropy loss, δ^(L) often simplifies to (a^(L) − y).

- Propagation: For l from L−1 down to 1, compute δ^(l) = (W^(l+1))^T δ^(l+1) ⊙ g′(z^(l)). This links the error in each layer to the next, scaled by the derivative of the activation.

- Parameter Gradients: ∂E/∂W^(l) = δ^(l) (a^(l−1))^T, ∂E/∂b^(l) = δ^(l). Update parameters using these gradients with learning rate α.

F) Importance of Data and Flexibility

- Data Scale: Deep learning performance typically improves with more high-quality data, as models can learn richer patterns and reduce overfitting risk via diversity.

- Flexibility: The same basic framework (layers + activations + gradient-based training) adapts to images (with CNN layers), sequences (with RNN layers), and more.

Tools/Libraries Used (Per Course Setup):

- Python: A general-purpose programming language favored for data science due to readability and rich ecosystem (NumPy, pandas, Matplotlib, etc.).

- TensorFlow: A deep learning framework handling tensor operations, automatic differentiation (autograd), and optimizers. High-level APIs let you define layers (Dense), models (Sequential/Functional), and training loops (fit) without manual gradient coding.

- Why Chosen: Strong community support, performance optimizations, and integration with hardware accelerators (GPUs/TPUs). It streamlines implementing the forward/backward computations discussed.

Step-by-Step Implementation Guide (Conceptual, aligned to lecture content):

- Define the Model Structure

- For a perceptron: decide input dimension d (number of features), choose an activation (sigmoid/ReLU/tanh), and initialize w ∈ R^d and b ∈ R.

- For an MLP: choose number of layers, units per layer, and activation per layer; initialize W^(l) and b^(l).

- Forward Pass

- Compute z = w^T x + b (perceptron) or z^(l) = W^(l) a^(l−1) + b^(l) for each layer.

- Apply activations to get a or a^(l) = g(z^(l)). Keep a^(l) and z^(l) for backprop.

- Compute Loss

- Compare predictions to true labels to get scalar loss E. For binary classification, often use a sigmoid on output and a cross-entropy style loss; for regression, MSE is common.

- Backward Pass (Backprop)

- Compute gradients of loss w.r.t. outputs, then recursively compute δ^(l) for each layer using chain rule and stored z^(l), a^(l−1).

- Get gradients ∂E/∂W^(l), ∂E/∂b^(l) for all layers.

- Parameter Update

- Update W^(l) := W^(l) − α ∂E/∂W^(l), and b^(l) := b^(l) − α ∂E/∂b^(l) for each layer. Repeat for multiple iterations/epochs.

- Evaluation and Iteration

- Monitor training loss and accuracy; check validation performance to ensure generalization. Adjust learning rate, model size, or data preprocessing as needed.

Tips and Warnings (Aligned with Concepts Introduced):

- Activation Choice: Start with ReLU in hidden layers for efficiency; use sigmoid/tanh if your task’s output needs bounded ranges. Beware of saturation with sigmoid/tanh; gradients can vanish when |z| is large.

- Learning Rate: Test a few α values; too large will cause divergence (loss explodes), too small will stall learning. Plot loss over iterations to diagnose convergence behavior.

- Initialization: While not detailed in the lecture, remember that poor initialization can hamper learning; common practice uses small random values to break symmetry.

- Overfitting and Regularization: The course will cover regularization later; for now, note that complex networks can memorize training data—monitor validation metrics.

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize or standardize inputs to help training stability; unscaled features can slow or destabilize gradient descent.

Connecting to Applications (Images, Language, Speech):

- Images: Replace fully-connected layers at the input with convolutional layers to exploit locality and translation invariance; still trained by backprop + gradient descent.

- Language/Speech: Use recurrent (or other sequential) layers to handle time dependencies; training loop remains forward + backward passes with parameter updates.

Putting It All Together—Mental Model:

- A neural network is a chain of affine transforms plus non-linear activations. Training repeatedly performs: forward pass → loss → backward pass → parameter update. Depth and non-linearity let the model learn hierarchical features. Enough data and thoughtful training make it powerful on complex tasks like vision, NLP, and speech.

04Examples

- 💡

Image Recognition Use Case: Consider recognizing cats vs. dogs in photos. A deep model first learns edges, then fur textures, then ear and snout shapes, finally deciding cat or dog. Input is pixel data; the network processes it layer by layer, producing a probability for each class. The output is a label like "cat" with high confidence. The point is how hierarchical features enable high accuracy.

- 💡

Self-Driving Car Vision: A CNN processes dashcam frames to detect pedestrians, traffic lights, and stop signs. Inputs are sequences of images; convolutional layers scan for learned patterns, and later layers classify objects. The output is bounding boxes and labels for road elements. This demonstrates deep learning’s ability to manage complex, variable visual scenes.

- 💡

Medical Image Analysis: Given MRI scans, deep models flag suspicious lesions. Input images go through layers that detect textures and shapes indicative of disease. The output is a heatmap or diagnosis suggestion. This example emphasizes real-world impact where sensitivity and accuracy are critical.

- 💡

Facial Recognition: The system compares a new face image to a database of known faces. Input pixels are transformed into embeddings (feature vectors) through deep layers. The output is the closest match or a verification score. This shows how learned representations capture identity-related features.

- 💡

Machine Translation: An RNN-based model reads a sentence in one language and outputs it in another. Inputs are word tokens or embeddings; the model maintains a hidden state to capture context. The output is a translated sequence word by word. This underlines the need for sequence modeling to preserve meaning and grammar.

- 💡

Chatbots: A model processes user messages and generates helpful responses. Inputs are text messages; the network encodes context and intent over turns. The output is a reply that fits the conversation. This illustrates how deep learning handles nuance in human dialogue.

- 💡

Text Summarization: The model reads a long article and produces a concise summary. Input tokens pass through layers capturing key points and structure. The output is a shorter text preserving the main ideas. This example shows abstraction capabilities over sequences.

- 💡

Speech Recognition: Audio waveforms are converted to text. Inputs are audio features like spectrograms; sequence models map time-varying sounds to characters or words. The output is a transcript such as "Set an alarm for 7 AM." This demonstrates temporal pattern learning.

- 💡

Perceptron Computation Flow: With input features x and parameters w, b, compute z = w^T x + b, then a = g(z). Inputs might be metrics like word counts or pixel intensities. The output a could be a probability or an activation passed to the next layer. This clarifies how a single neuron processes information.

- 💡

Gradient Descent Update Step: After computing the loss, calculate ∂E/∂w and ∂E/∂b. Update w := w − α ∂E/∂w and b := b − α ∂E/∂b. Inputs are the current parameters and gradients; the output is improved parameters for the next iteration. The key lesson is that small, repeated updates reduce error over time.

- 💡

MLP Layer Stacking: Start with a^(0) = x, compute z^(1), a^(1), z^(2), a^(2), up to a^(L). Inputs are feature vectors; hidden layers transform them non-linearly. The output layer produces the final prediction, such as class probabilities. This example shows how depth builds complex mappings.

- 💡

Activation Function Behavior: Feed z values through sigmoid, ReLU, and tanh to see outputs. Inputs like z = −2, 0, 2 produce different shaped outputs depending on activation. Outputs illustrate saturation (sigmoid/tanh) and zeroing negatives (ReLU). The lesson is that activation choice affects gradient flow and learning.

- 💡

Backpropagation Pass: After a forward pass computes loss, calculate output error δ^(L) and propagate backward. Inputs are stored activations and weights; outputs are gradients for each W^(l) and b^(l). This yields parameter updates for every layer. The key idea is efficient gradient computation using the chain rule.

- 💡

Course Workflow Example: Homework asks you to implement an MLP for a small dataset. Inputs are data and labels; you write code for forward pass, loss, and parameter updates in TensorFlow. The output is a trained model with reported accuracy. This demonstrates the blend of theory and practical coding expected in CS230.

- 💡

Office Hours/Forum Support: You struggle with a learning rate that causes divergence. Inputs are your training logs and code snippets; you ask on the forum or attend office hours. The output is targeted advice—reduce α and normalize inputs. This example shows how course resources help you overcome blockers.

05Conclusion

This first CS230 lecture sets the tone, scope, and foundation for mastering deep learning. You learned that deep learning uses multi-layer neural networks to learn hierarchical, non-linear representations, which is why they work so well for complex tasks like image recognition, natural language processing, and speech recognition. The technical core introduced the perceptron (z = w^T x + b, a = g(z)), emphasized the necessity of non-linear activation functions (sigmoid, ReLU, tanh), and explained gradient descent as the engine that updates weights and bias to minimize error. Extending to multi-layer perceptrons, you saw how stacking layers transforms simple operations into powerful function approximators. Backpropagation ties everything together by efficiently computing gradients layer by layer through a forward and backward pass.

On the course roadmap, expect a balanced blend of theory and practice: Part 1 (foundations: neural networks, backpropagation, optimization, regularization), Part 2 (CNNs for images, object detection, segmentation), and Part 3 (RNNs for sequences: language, speech, time series). Plan for a steady workload with four coding homeworks, a theory-focused midterm, and a real-world final project, graded 40% homeworks, 20% midterm, and 40% final project. You’ll use Python and TensorFlow and get support through office hours and an online Q&A forum.

To practice right away, review the neuron equations, experiment with simple activations on toy inputs, and implement a minimal perceptron or tiny MLP. Try different learning rates to see how convergence changes, and get comfortable inspecting losses and predictions. As next steps, be ready to dive deeper into backpropagation derivations, then into CNNs for vision and RNNs for sequences.

The core message to remember is that deep learning’s strength lies in learning layered, non-linear features from data and improving through gradient-based optimization. With consistent effort, smart use of course resources, and a clear understanding of the fundamentals you learned today, you’ll be equipped to build models that solve meaningful, real-world problems in vision, language, and speech.

Key Takeaways

- ✓Start with the neuron mental model: weighted sum plus bias, then a non-linear activation. Always write out z = w^T x + b and a = g(z) when debugging. Check if your inputs are sensible and if activations are saturating. This simple equation explains most training behaviors you’ll see.

- ✓Non-linearity is not optional—choose activations thoughtfully. ReLU is a strong default for hidden layers due to efficiency and gradient flow. Use sigmoid or tanh only when their output ranges are needed or helpful. Watch for saturation with sigmoid/tanh and dead neurons with ReLU.

- ✓Tune the learning rate early. If loss explodes, lower α; if loss barely moves, increase it modestly. Plot loss across iterations to see trends clearly. A good α makes training stable and fast.

- ✓Stack layers to learn hierarchy, but keep it reasonable. More layers increase capacity but also training difficulty and overfitting risk. Start shallow and scale complexity as needed. Monitor validation performance to guide depth and width.

- ✓Use forward/backward pass thinking for every bug. If outputs look wrong, inspect activations layer by layer (forward). If learning stalls, verify gradients exist and have reasonable magnitudes (backward). This structured approach quickly isolates issues.

- ✓Plan your time—this course is demanding by design. Break homeworks into phases: data prep, model build, training, evaluation, and report. Seek help early at office hours or the forum when blocked. Small daily progress beats last-minute marathons.

- ✓Build a minimal working model first. Implement the simplest perceptron or tiny MLP to verify your pipeline. Once it learns something, scale up architecture and training time. This reduces wasted effort debugging big models.

- ✓Mind your data preprocessing. Normalize or standardize features so gradients behave well. Unscaled inputs can make learning rates tricky. Clean data often matters as much as fancy models.

- ✓Use clear evaluation practices. Track training and validation metrics to detect overfitting. Don’t rely on training accuracy alone. Keep logs and plots to compare runs fairly.

- ✓Document your experiments. Record model settings, learning rates, and results. Reproducibility saves time and helps you learn patterns in what works. This habit is crucial for the final project.

- ✓Lean on Python and TensorFlow to move fast. High-level layers and automatic differentiation reduce boilerplate. Focus your energy on model design and data. Understand enough of the math to interpret what the code is doing.

- ✓Connect architectures to data types. Use CNN ideas for images and RNN ideas for sequences. The training loop stays the same—forward, loss, backward, update. Picking the right structure multiplies your chances of success.

- ✓Measure twice, train once. Sanity-check shapes, initial losses, and a single forward pass before long training runs. Catching shape or activation mistakes early prevents hours of wasted compute. A five-minute check can save a day.

- ✓Think in terms of decision boundaries. If your task clearly needs curved separations, a single linear layer won’t do. Add hidden layers and non-linear activations to capture complexity. Use visualizations on toy data to build intuition.

- ✓Use the forum and office hours strategically. Prepare focused questions with code snippets and logs. You’ll get faster, more precise help and learn from others’ patterns. Teaching assistants and peers are powerful multipliers.

- ✓Embrace iteration. Expect to try multiple learning rates, activations, and layer sizes. Each run teaches you something about the problem. Iteration with reflection is how you get to a robust final project.

- ✓Keep the big picture: hierarchy + non-linearity + gradient-based training. This trio explains why deep learning works across vision, language, and speech. When in doubt, return to these pillars. They guide both theory and practice.

Glossary

Deep Learning

A kind of machine learning that uses many layers of simple math units (neurons) to learn complex patterns. Each layer turns inputs into slightly more useful forms, step by step. By stacking many layers, the system can handle hard tasks like seeing objects in images or understanding speech. It learns from examples instead of being told exact rules. More data usually helps it get better.

Machine Learning

A way for computers to learn from data rather than by following only hand-written rules. The computer looks for patterns linking inputs to outputs. Over time, it adjusts its internal settings to make better predictions. This helps solve problems that are too tricky to program by hand.

Neural Network

A network of simple units called neurons that each do a small calculation and pass results forward. Many neurons and layers together can learn tough patterns. The network adjusts weights and biases to improve. Non-linear activations let it learn curves, not just straight lines.

Perceptron

The simplest type of neuron that sums inputs times weights, adds a bias, and applies an activation function. It’s a tiny decision-maker. By itself it can only draw straight-line decisions. It is the building block for deeper networks.

Activation Function

A mathematical function applied to a neuron’s input to add non-linearity. It helps the network draw curves and make complex decisions. Without it, many layers would still act like one straight-line model. Common choices are sigmoid, ReLU, and tanh.

Sigmoid

An S-shaped activation function that outputs numbers between 0 and 1. It’s useful when you want a probability-like output. But for very large or very small inputs, its slope gets tiny and learning can slow. It is smooth and simple.

ReLU

Stands for Rectified Linear Unit. It outputs zero for negative inputs and the input value for positive inputs. It’s fast and helps deep nets learn by avoiding very small gradients on positive values. Some neurons can become inactive if inputs stay negative.

Tanh

A squashing activation that outputs between -1 and 1. It is like a shifted sigmoid that’s centered at zero. It can still suffer from small gradients when inputs are very large in magnitude. Zero-centered outputs can make learning smoother.

+30 more (click terms in content)